Physical Therapy Intervention to Provide For Safe Return To Activity

As discussed in the previous article on this topic, ACL injury is a very common and debilitating condition. ACL injuries are four to six times more common in female athletes competing in the same sports activities as males. Treatment of ACL injuries can be costly from an economic standpoint – conservative estimates for a single episode of surgery and post-operative treatment range between $17,000-25,000 – as well as have other significant detrimental long-term effects, including decreased academic performance and a 105 times greater risk for radiographically diagnosed osteoarthritis.

As discussed in the previous article on this topic, ACL injury is a very common and debilitating condition. ACL injuries are four to six times more common in female athletes competing in the same sports activities as males. Treatment of ACL injuries can be costly from an economic standpoint – conservative estimates for a single episode of surgery and post-operative treatment range between $17,000-25,000 – as well as have other significant detrimental long-term effects, including decreased academic performance and a 105 times greater risk for radiographically diagnosed osteoarthritis.

As mentioned previously, several modifiable risk factors have been identified that place the female athlete at greater risk for ACL injury than males. Below are the significant risk factors according to research performed by Hewitt and colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. Also included are various intervention strategies and techniques that can be implemented by physical therapists to decrease the risk for re-injury upon the athlete’s return to sport.

Ligament Dominance: characterized by the tendency to absorb ground reaction forces with static tissues (i.e., ligaments, bone and cartilage) rather than muscular tissue, placing ligamentous tissues including the ACL, at greater risk for injury. Physical therapists can best address this factor by providing appropriate verbal and visual feedback during tasks that place greater stress on the knee joint, such as jumping and cutting/pivoting. Of major importance is the correction of “valgus collapse”, or the tendency for the knee(s) to bow inward toward each other while under load.

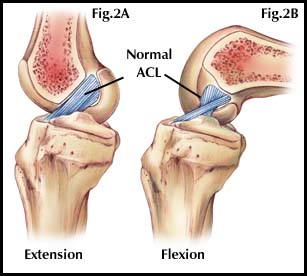

Quadriceps Dominance: defined by the tendency to initiate muscle contraction of the quadriceps (front of the thigh) earlier and with greater force than the hamstrings (back of the thigh), again resulting in greater strain on the ACL. Physical therapists can prescribe exercises to facilitate the “posterior kinetic chain” musculature (hamstrings, gluteals) to provide a counter-acting force to limit excessive anterior translation of the shin-bone (tibia) on the thigh-bone (femur), reducing stress on the ACL. Training can also take place that increases the amount of knee bending (flexion) during landing activities, again unloading the ACL.

Leg Dominance: females demonstrate a greater likelihood to favor one leg over the other during jumping and landing tasks, placing significantly greater strain on one limb. Training with single limb tasks (balance, strengthening) helps reduce asymmetry between limbs, reducing risk for knee injury.

Trunk Dominance: characterized by the lack of torso control and the greater likelihood for females to allow their center of mass (generally located within the trunk of the body) to travel outside their base of support. As the torso moves laterally, or sideways, from the legs, strain on the ligamentous structures greatly increases. Physical therapists address deficiencies in trunk stability with exercises focused on improving strength and facilitation of the abdominal, low back, lateral and posterior hip musculature.

Return to Sport Criteria

Frequently, athletes can be under great stress, either self-imposed, or by parents and coaches, to return to sport quickly following ACL injury. In many cases, the athlete’s subjective rating of their functional ability does not accurately reflect their true physical capabilities – in other words, they think they’re better than they actually are. Objective testing can be a valid tool to detect decreased physical performance and assess whether an athlete has the physical capacity to more safely return to sport. Studies have looked at different physical assessments to gauge readiness, and have consistently shown long-term asymmetry in the ability of the involved extremity to attenuate, or absorb, force as efficiently as the uninvolved limb. Several tests have been shown to assess limb asymmetry accurately – these include several variations of single leg hopping, including the single hop for distance, the three hop test for distance, and the cross-over three hop test. Each of these tests measure the ability of the involved limb to generate power, then absorb forces efficiently in a controlled and balanced manner. Athletes that are able to perform these tasks within at least 85-90% of the uninvolved limb show a significantly decreased risk for re-injury upon return to their sporting activities.

The role of the physical therapist is to provide for the best outcome for their patient. With the individual having undergone ACL reconstruction, physical therapists have the unique skills and knowledge to develop a challenging and rigorous program to address common risk factors that have likely placed the athlete at greater risk for injury initially, as well as provide appropriate assessment and training to reduce the risk of re-injury upon return to sport.

References:

Hewett,T, et al. “Understanding and preventing ACL injuries: current biomechanical and epidemiologic considerations – update 2010”. North American Journal of Sports Physical Therapy. Dec. ’10, v. 5(4) 234-251.

Myer, G, et al. “Utilization of modified NFL combine testing to identify functional deficits in athletes following ACL reconstruction”. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy. June ’11, v. 41(6) 377-387.