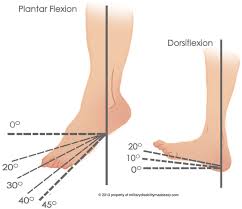

Recent articles in this series have discussed various conditions affecting the lower leg and foot, specifically Achilles’ tendon injuries, ankle sprains and plantar fasciitis. All of these conditions manifest as pain in different areas of the lower extremity, yet they all have a common link. The shared common factor among these conditions is limited ankle dorsiflexion, or the ability of the distal foot to move upward toward the shin (“toes to nose”). Limited dorsiflexion is commonly seen following ankle sprains and fractures, especially when a period of immobilization follows trauma. This limited mobility can also set the stage for dysfunction (and pain) in other areas of the body, as the body functions as a “kinetic chain”, or an interconnected series of levers and joints. However, limited ankle dorsiflexion is not the only “guilty party” that has a tendency to affect other regions. Limited joint mobility, weakness of specific muscles, or excessive mobility can all have negative effects inother areas of the body.

Within the last decade in physical therapy, a paradigm shift has been occurring, with increased attention being given toward how the body moves as a whole, and how function of one area affects that of another region. The term, “regional interdependence” (RI), refers to the concept that “seemingly unrelated impairments in a remote anatomical region may contribute to, or be associated with, the patient’s primary complaint” (Wainner , ’07). Used in conjunction with the more traditional biomedical model, in which a specific tissue or process is diagnosed as being a generator of pain (e.g., “Achilles’ tendinitis” or “herniated disc”), assessment by the physical therapist utilizing concepts of RI allows for a more thorough, and potentially effective, treatment plan and intervention.

Using the above example of limited ankle dorsiflexion, we can see that effects occur both above and below the ankle. In the case of plantar fasciitis, limited ankle motion causes the individual to rise up onto the toes of the affected foot prematurely, leading to increased loading of the plantar fascia. Increased load, repeated thousands of times daily with walking, results in an inflammatory response and pain atthe plantar fascia attachment into the heel bone at the bottom area of the foot.

Limited ankle dorsiflexion can also have a negative affect up the kinetic chain. Recent studies have shown that patellar tendinitis, also known as “jumper’s knee”, is commonly seen in patients who lack appropriate ankle dorsiflexion. Limited motion at the ankle can result in less than optimal jumping and landing mechanics, such as decreased bending (“flexion”) of the knees, thought to increase stress within the patellar tendon, again resulting in inflammation and potential tendon breakdown.

Other conditions in which studies have linked more remote areas as playing a role in the injury process include patellofemoral pain syndrome (foot and hip mechanics affecting the knee), cervicalgia and rotator cuff disorders (decreased joint mobility at the midback, or thoracic spine, affecting the proper mechanics of the neck and shoulder).

Physical therapists, trained as movement specialists, have the ability to assess the body both locally, utilizing evaluation skills to identify damaged tissue (e.g., ligament stability tests, palpation skills, etc.), and globally, using the concept of regional interdependence. In doing so, the PT can effectively find and address the causes of pain and faulty movement, the end result being a successful return to full function.